At the Senate Hearing on Capitol Hill in July of this year, representatives of Five Tribal Nations, addressed the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs on issues pertaining to the Freedmen of the Five Tribes. I attended that hearing, and sat directly behind the speakers. It was quite disappointing to listen to the words of the Choctaw Nation representative. Mr. Michael Burrage who made the statement that Choctaw citizenship is an issue about blood, and not about race.

Was Attorney Burrage speaking from what he truly believed to be true? Was he simply giving spin that he is paid to give? Or was he possibly honestly unaware of cases where numerous people identified as "Freedmen" had Choctaw fathers---who have the blood he spoke about. Is he not aware that they are still considered to be outsiders and not welcomed?

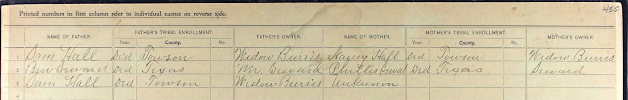

Here is such an example of a Freedman who had Choctaw blood.

Ardena Darneal, Daughter of a Choctaw Indian:

This is a case where the daughter of a well-known Choctaw was not put on the blood roll, nor was her mother able to place her on the roll of the tribe to which her daughter was born. Because her mother's line came from Chickasaws slaves. The name of Ardena Darneal is actually found on a Chickasaw Freedman Card. But Ardena had a Choctaw father.

On the front of the Dawes enrollment card, a note appears about Ardena's mother Fanny. The hand-written note clearly states that the mother Fanny Parks, is "Separated from Silas Darneel, a Choctaw Indian."

Some time ago, Verdie Triplett, the grandson of Ardena Darneal, applied for citizenship in the Choctaw Nation. He was denied. He applied because he has a proven lineage by blood to a known Choctaw. He submitted all required documents including the card referring to Ardena's father. He proved in his application that he had the "blood" that Attorney Burrage spoke about. But yet, he was denied, even though lineal descent was proven.

Was it because the mother Fanny was on a Chickasaw Card? But her card proved the blood tie of her daughter to a still living Choctaw, and Ardena was the daughter of a Choctaw Indian. And if Verdie Triplett can prove that he is a lineal descendant of Silas Darneal a Choctaw and that he has the frequently mentioned blood---why is he not a citizen?

Was it because the child's father did not put her on his card? That can't be the case,because Fanny, the Freedwoman was not allowed to enter the tent of blood citizens, even though her daughter clearly had her father's blood. Attorney Burrage states, the case has to be proven of lineal descent. Mr. Triplett proved lineal descent through vital records connecting him directly to Ardena. And it is clear that Fanny Park's Ardena's mother told the Commission, who the child's father was and a notation was recorded on the card. Lineal descent was proven. Ardena had Choctaw blood, but was never put on the blood roll. But the question then arises: What is wrong with Ardena's blood?

Or------------is it possible that the issue is in reality, one of race and not blood? Indeed this question must be asked, because in case after case, those with Choctaw fathers were not admitted. The one thing in common that they had was that in almost every case, the mother was of African descent. The race of the mother extended to the child and was then used against them, thus preventing Ardena, and all of her descendants from Choctaw citizenship forever. But Ardena was clearly one-half Choctaw and the attorney told the Senate Committee on Indian Affair, that lineal descent must be proven and that it is all about blood!

Attorney Burrage pointed out that there are black people who are members of the tribe. But he did not point out that these are descendants of inter-racial marriages that have occurred in recent years.

The final reason to exclude Freedmen when all other excuses are exhaustd is the use of the word, "sovereignty." Is sovereignty a "code word" for the right to exclude the very people who were enslaved in the same nation? Is that the action of an honorable and "proud" people?

Ardena Darneal, like her mother Fanny was put on the final roll as a descendant of slaves. Her blood tie to a Choctaw meant nothing to the Dawes Commission and it means nothing to the Choctaw Nation, today. Her placement on the Freedmen roll also meant that she would only receive 1/8th the amount of land that blood-roll citizens were given.

In other words, blood-roll Choctaw were allotted 8 times more land (320 acres) than their former slaves (40 acres). And now today, descendants of "blood-roll" Choctaws are still punishing the descendants of those they enslaved by not even giving them citizenship in the land where their ancestors lived, toiled and died.

In fairness, is it possible that today's tribal officials are simply unaware of these cases? If so, then shouldn't this issue be reviewed to right a wrong?

Would Attorney Burrage not agree that Ardena Darneal's blood tie is there, and that Mr. Triplett and his children are deserving of citizenship?

Mr. Triplett still lives in the same neighborhood in Le Flore County that his Darneal cousins who are Choctaw citizens live. They know each other as cousins, but yet "sovereignty" or prejudice does not allow one part of Silas Daneal's descendants to be recognized a citizens while others from the same man, are citizens. Yet they are ALL Choctaw people.

Would be Mr. Burrage become an advocate for descendants of this half Choctaw child to be a citizen today? Sadly, this is not the only case, for there are so many more.

A Question of Morality

Why not address the moral issue of mistreating former slaves and their descendants?

The immorality of the policy of a blood tie should be addressed. When it comes to the right of citizenship of a people held in bondage for generations, how can the composition of their blood cast them out of a place that their ancestors earned?

A question to Attorney Burrage---are you truly comfortable with that?

Choctaw Freedmen had the same home as those on the blood roll and the roll of "inter-married whites" with whom the tribe has no issue. The Freedmen had no other home! The Freedmen themselves had been immersed in the same culture, language, foodways and had to abide by the same laws. So how canone justify denial of a people who were a Choctaw people, because they don't have the slave owner's blood?

To the Choctaw Nation---Is that who you really are? The policy based on looks and blood---when the former slaves had no other home is a racist policy, a cruel policy and vicious policy! If that is the case, and if that is what you are, then come forth in your truth and speak to it. On the other hand, if that is not the spirit of the Chahta Proud, then exhibit the courage of the ancestors and do what is right.

The country that funds the Choctaw Nation is the United States. And the United States did not stipulate in the 14th Amendment that former slaves had to have the blood of their slave holders to be American citizens. So how does the Choctaw Nation practice and consider their blood policy to be one of sovereignty or intergrity, or righteousness? Especially even when Freedmen descendants prove their blood ties--they are still denied.

Does the Choctaw Nation wish to truly be recognized as a community embracing prejudices of the Old South? If so, say so and let the world know that is who you are. If that is not who you wish to be, then reach back to the hands that reached back to you, in 2021, resulting from Chief Batton's Open Letter.

Doing the right thing is not that hard.